Building ooIDE: Spatial Computing for AI Development

A technical deep-dive into ooIDE spatial development framework and how we unified a 3D virtual office with MCP aggregation, dual-memory architecture, and git worktree isolation to eliminate AI development fragmentation.

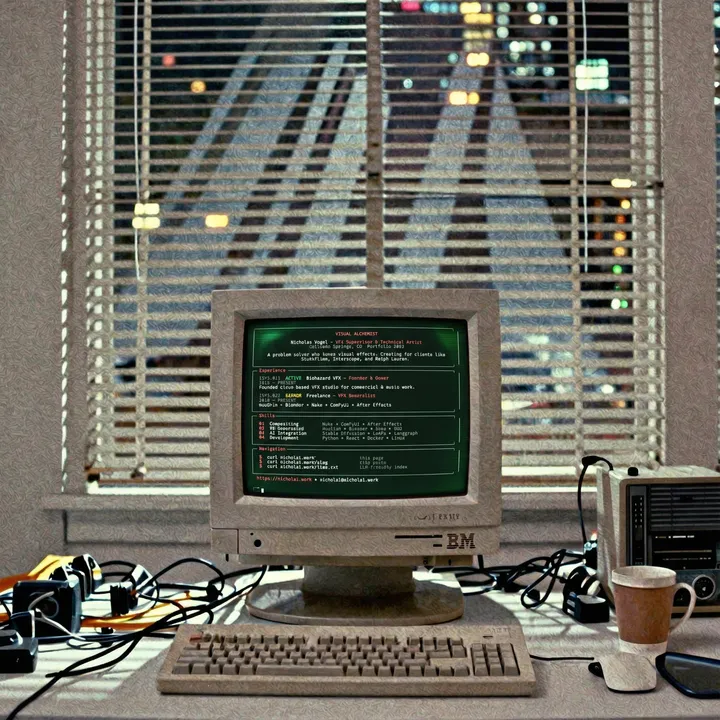

The Context-Switching Nightmare

I’m sitting at my desk with two AI tools open: Claude Code for backend work, Cursor for frontend. Each one has a different MCP configuration file. Each one needs the same context explained again. Each one forgets what the other learned.

I copy a decision from Claude Code’s conversation into a note. Five minutes later, Cursor asks me the same architectural question. I explain it again. I’m copy-pasting context between tools like some kind of human context bus.

“Why did we choose Drizzle over Prisma?” I don’t remember. It was three sessions ago. The code shows what we did, but the why is gone. Lost in some previous conversation that’s now sitting in a closed browser tab somewhere.

This is the fragmentation problem. Every AI tool is an island. No shared memory. No persistent decisions. No way to say “this is the canonical answer to that question” without writing it down somewhere manually. And if you do write it down, the AI tools can’t access it unless you paste it into every conversation.

It’s exhausting.

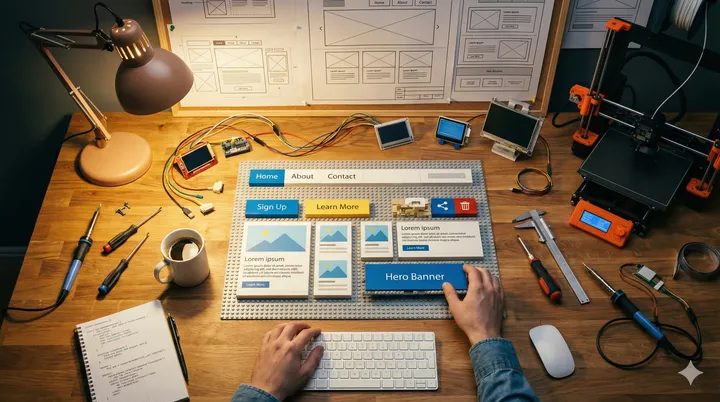

What If Your Codebase Was A Place?

Here’s the idea that became ooIDE: what if your entire development environment was a 3D office you could walk through? What if context wasn’t something you copy-pasted, but something that lived in space?

Walk into the backend zone—your AI suddenly knows about the database schema, the API contracts, the architectural decisions made last week. Walk into the frontend zone—context shifts to component patterns, state management, the design system. Not because you explained it, but because the space carries that information.

The office isn’t just a gimmick. It’s a navigation paradigm. Spatial memory is how humans naturally organize information. We don’t remember file paths—we remember “that file I was working on in the corner of the project.” We don’t think in directory trees—we think in zones, areas, neighborhoods of related work.

And here’s the critical part: all your AI tools connect to the same server. One MCP configuration. One memory system. One source of truth. Claude Code, Cursor, and any other MCP-compatible tool—they all share the same workspace, the same context, the same memory of what happened yesterday.

So we built that.

The Trinity: Visual, Physical, Temporal

The core innovation of ooIDE is what we call the “trinity of representation.” Every zone in your workspace exists simultaneously in three states:

Visual (Godot 3D): The office you see on screen. Walkable. Interactive. Visually distinct zones that reflect the type of work happening there. Server infrastructure looks industrial. Creative design areas have warm lighting. Test environments feel clinical. The visuals aren’t arbitrary—they map to the function of the code.

Physical (Filesystem): Standard directories your IDE and CLI tools already use. No magic. No vendor lock-in. It’s just folders with a .zoneattributes.json sidecar file that bridges the gap between your filesystem and the 3D world. Open the folder in VS Code—it works normally. Run git status—it works normally. The spatial interface wraps your existing workflow, doesn’t replace it.

Temporal (Git): Version history through worktrees. Multiple agents can work in parallel, each in isolated worktrees, without stepping on each other’s toes. A global lock manager prevents race conditions. When work finishes, changes get merged back. All managed automatically.

This trinity isn’t just conceptual—it’s how the system actually works. The Godot client procedurally generates the office from your filesystem structure. When you create a new directory, a new zone appears in the office. When you commit changes, the temporal layer captures not just what changed, but why—in a PostgreSQL decision log that becomes institutional memory.

Projects, Zones, and Primitives

Here’s where things get technical. The spatial framework follows a hierarchy:

Projects are the top-level containers. Think of them as buildings in your virtual office complex. Each project might be a monorepo, a microservice cluster, or a collection of related tools.

Zones are functional workspaces within projects. These are the rooms in your office. A zone could be:

- A service subdirectory (your auth service, your API gateway)

- A git worktree (parallel work streams)

- A feature branch isolated for agent development

Each zone has attributes defined by a Zod schema:

// Zone attributes schema

export const ZoneAttributesSchema = z.object({

zone_id: z.string().describe('Unique identifier'),

coordinates: z.object({

x: z.number(),

y: z.number(),

z: z.number(),

}).describe('Spatial position in the 3D world'),

dimensions: z.object({

chunks: z.number().min(4).describe('Minimum 4 chunks for circulation space'),

}),

capabilities: z.array(z.string()).describe('Available tools/languages in this zone'),

primitives: z.object({

visual_theme: z.string().describe('Godot theme identifier'),

agent_prompt: z.string().describe('Path to behavioral prompt file'),

conventions: z.string().describe('Path to CLAUDE.md or equivalent'),

}),

git: z.object({

is_worktree: z.boolean(),

branch: z.string(),

}).optional(),

});Primitives are the DNA of a zone. They define:

- Visual appearance (theme, layout, lighting)

- Agent behavior (which system prompts apply here)

- Conventions (CLAUDE.md files, coding standards, architectural patterns)

The schema serves three purposes simultaneously:

- Validation: TypeScript types inferred from Zod ensure compile-time safety

- Runtime checks: Invalid configurations get caught before they break anything

- AI constraints: The schema itself becomes a prompt that tells agents what actions are valid

This is the “catalog pattern”—a single source of truth that eliminates drift between what the code expects, what the AI understands, and what the user configures.

The Sidecar Pattern

Every zone directory has a .zoneattributes.json file. It’s tiny—just metadata:

{

"zone_id": "auth-service-01",

"coordinates": { "x": 10, "y": 0, "z": -5 },

"dimensions": { "chunks": 6 },

"capabilities": ["typescript", "postgresql", "docker"],

"primitives": {

"visual_theme": "industrial_complex",

"agent_prompt": "./prompts/backend_specialist.txt",

"conventions": "./CLAUDE.md"

},

"git": {

"is_worktree": true,

"branch": "feature/refactor-auth"

}

}When Godot loads, it reads all these sidecar files and generates the office layout. When an agent enters the zone, the MCP server reads the sidecar and adjusts:

- Which tools are available (RAG retrieval weights toward

typescript,postgresql,docker) - Which conventions apply (loads

./CLAUDE.mdas system prompt) - Which visual theme renders (industrial aesthetic for backend infra work)

The formula for chunk allocation is S = 4 + n, where S is total chunks and n is the number of agents. Four chunks provide “circulation space”—hallways, common areas, infrastructure. Each additional agent needs 1 dedicated workspace chunk to avoid coordinate collisions.

A zone with 2 agents working simultaneously needs at least 6 chunks. The system enforces this at the schema level.

Prompt Generation from Schema

The catalog doesn’t just validate—it generates prompts. Here’s how a zone’s attributes become AI instructions:

// Prompt generation from zone attributes

export function generateZonePrompt(zone: z.infer<typeof ZoneAttributesSchema>): string {

return `

You are operating within zone "${zone.zone_id}".

## Spatial Context

- Location: (${zone.coordinates.x}, ${zone.coordinates.y}, ${zone.coordinates.z})

- Available space: ${zone.dimensions.chunks} chunks

## Capabilities

You have access to the following tools and languages:

${zone.capabilities.map(c => `- ${c}`).join('\n')}

## Behavioral Constraints

Your behavior is governed by: ${zone.primitives.conventions}

## Output Format

When modifying zone state, respond with valid JSON matching the ZoneAttributes schema.

Do not introduce capabilities or actions not listed above.

`;

}The AI literally cannot suggest actions outside the catalog. If the zone doesn’t list rust as a capability, the agent won’t try to run cargo commands. If the zone’s conventions file says “never push to main,” that constraint is injected into every prompt.

It’s a leash, but a useful one.

The Architecture Stack: MCP Aggregation

The spatial interface is the frontend. The real technical work happens in the backend: MCP aggregation with namespace collision resolution.

The Problem

Without ooIDE, here’s what your MCP setup looks like:

Claude Code needs ~/.config/claude/claude_code_config.json:

{

"mcpServers": {

"supabase": { "command": "npx", "args": ["-y", "supabase-mcp"] },

"stripe": { "command": "npx", "args": ["-y", "stripe-mcp"] }

}

}Cursor needs .cursor/mcp.json:

{

"servers": {

"supabase": { "command": "npx", "args": ["-y", "supabase-mcp"] },

"stripe": { "command": "npx", "args": ["-y", "stripe-mcp"] }

}

}Two files. Two tools. Same configuration. When you add a new MCP server, you update both. When you change an API key, you change it twice. When two servers happen to have a tool with the same name? You’re on your own.

The Solution: Namespace-Based Routing

ooIDE runs a single MCP aggregation server. All your AI tools connect to it. It handles the namespace collision resolution and routes requests to the appropriate upstream MCP server.

Here’s the core routing logic:

// src/backend/src/services/mcp-router.ts (simplified)

class MCPRouter {

private servers = new Map<string, RegisteredMCPServer>();

resolveToolRoute(toolName: string): ToolRoute | null {

// Check for namespaced tool (server_id:tool_name)

if (toolName.includes(':')) {

const [namespace, serverToolName] = toolName.split(':');

for (const [serverId, server] of this.servers) {

if (serverId === namespace || server.name === namespace) {

const tool = server.tools.find(t => t.name === serverToolName);

if (tool) {

return {

toolName,

serverId,

serverToolName,

hasNamespace: true,

namespace,

};

}

}

}

}

// Fallback: find all servers that have this tool

const availableServers = [];

for (const [serverId, server] of this.servers) {

if (server.tools.find(t => t.name === toolName)) {

availableServers.push({ serverId, serverName: server.name });

}

}

// Use load balancer to select best server

return mcpLoadBalancer.selectServer(toolName, availableServers);

}

}When two MCP servers both expose a read_table tool, ooIDE automatically namespaces them: supabase:read_table and airtable:read_table. The AI sees both tools. You choose which one to use. No collision. No confusion.

If a tool name is unambiguous (only one server provides it), you can call it without the namespace. If it’s ambiguous, you must use the namespace or let the load balancer pick for you.

The router also handles:

- Health checks on upstream servers

- Automatic failover if a server becomes unavailable

- Load balancing across redundant servers

- Metrics collection (Prometheus-compatible)

Dual-Memory Architecture

Context isn’t just code—it’s decisions. ooIDE uses two memory systems:

Temporal Memory (PostgreSQL): The narrative. Why decisions were made. What alternatives were considered and rejected. What failed in the past. This is the institutional memory that prevents repeating mistakes.

Schema snippet:

// Decision log table

export const decisionLog = pgTable('decision_log', {

id: serial('id').primaryKey(),

timestamp: timestamp('timestamp').defaultNow(),

decision: text('decision').notNull(),

context: text('context'),

alternatives_considered: text('alternatives_considered'),

rationale: text('rationale'),

made_by: varchar('made_by', { length: 50 }),

zone_id: varchar('zone_id', { length: 100 }),

});Semantic Memory (QDrant): The knowledge. What the codebase contains. API contracts. Code examples. Documentation. Vector embeddings enable RAG retrieval weighted by the zone you’re in. When you’re working in the frontend zone, frontend-related code chunks get higher relevance scores.

Together, these systems create persistent context that survives session restarts. An agent spawned today can access decisions made last week. The office has institutional knowledge.

Git Worktree Isolation

Multiple agents working in parallel is a recipe for merge conflicts. ooIDE solves this with git worktrees: each agent gets an isolated checkout of a specific branch. They can work simultaneously without interfering.

When work finishes, a worktree manager:

- Commits changes with an auto-generated message

- Pushes to a feature branch

- Opens a PR (optional)

- Cleans up the worktree

A global lock manager prevents race conditions when multiple agents try to access shared resources (like the main .git directory).

The Development Journey

We built ooIDE because the fragmentation problem was real. I was maintaining multiple MCP configs. I was repeating context across tools. I was forgetting why I made decisions two days ago. It was inefficient and frustrating.

This project represents the culmination of lessons learned from building tools with AI assistance—the shift from writing every line of code myself to orchestrating AI agents with clear specifications and detailed context. That “context engineering” approach became critical when designing ooIDE’s architecture.

The initial vision started with a 2D office in Phaser.js. The idea was simple: represent your codebase as an isometric space you could navigate. But Phaser is a browser game framework, not a full game engine. We hit limitations quickly:

- No built-in 3D support

- Limited pathfinding capabilities

- Procedural generation required custom systems

- Physics and collision detection felt bolted-on

We needed more power.

The Move to Godot

Godot 4 changed everything. It’s a real game engine with proper 3D support, built-in pathfinding, spatial audio, and a visual scripting system for agent behaviors. The decision to go 3D opened up possibilities:

- Vertical space for organizing zones

- Better sense of place and navigation

- Procedural generation using Godot’s SurfaceTool

- Natural spatial audio cues

- Proper lighting and atmosphere

The office went from a flat isometric grid to an actual 3D environment. Not photorealistic—we’re aiming for stylized, readable spaces—but spatial in a way 2D never could be.

Key Technical Decisions

Bun over Node.js: TypeScript-first runtime. Faster package management. Native WebSocket support. The developer experience is just better.

Drizzle over Prisma: Prisma is great but the bundle size is prohibitive for our use case. Drizzle is lighter and plays nicely with Bun. The SQL-like query builder also makes it easier to write complex joins without fighting an ORM.

Schema-First with Zod: This was critical. The Zod schemas became the source of truth for validation, type inference, and prompt generation. One schema, three uses. No drift.

MCP Aggregation Server-Side: We initially considered client-side routing but quickly realized a centralized server was the only way to handle namespace collisions properly and maintain a single source of truth.

Challenges We Hit

Phaser.js Limitations: The 2D framework couldn’t scale to what we needed. Moving to Godot meant rewriting everything but gave us the power we needed.

Godot Learning Curve: GDScript is different from TypeScript. The scene system, signals, and node architecture took time to understand. But once it clicked, the productivity gains were massive.

Namespace Collision Detection: Turns out it’s not enough to check tool names. Two servers can have identically-named tools with different parameter schemas. We had to implement deep schema comparison to catch these cases.

Multi-Worktree Git Complexity: Git worktrees share the .git directory, which means simultaneous operations can corrupt state if you’re not careful. We implemented a lock manager that queues operations and ensures only one worktree touches .git at a time.

RAG Retrieval Weighting: Getting the zone-based weighting right required manual tuning. Cold start problem: when a zone has no prior interactions, we don’t know which chunks are relevant. We’re still iterating on this.

What We’d Do Differently

Skip Phaser Entirely: Should have started with Godot. The 2D phase was exploratory but cost us time.

Server-Side from Day One: Any alternative to centralized MCP aggregation was a dead end.

PostgreSQL for Everything: We experimented with Redis for sessions and caching. PostgreSQL handles it fine and simplifies the stack.

Current Status and What’s Next

ooIDE is alpha software. It works, but there are sharp edges.

What Works Today:

- Frontend scaffold with 3D office rendering in Godot

- Backend API with WebSocket support for real-time updates

- MCP aggregation with namespace collision detection and load balancing

- Basic chat interface for AI interactions

- Database schema with decision log, temporal memory, task history

- Git worktree manager (functional but needs polish)

- Zone discovery system that auto-generates

.zoneattributes.jsonfrom your filesystem

What’s Next:

- Voice input: Push-to-talk integration for natural conversation (like a radio)

- Proactive monitoring: System that notices issues (failing tests, outdated dependencies) and surfaces them

- Multiplayer support: Multiple users in the same office, collaborating with their own AI tools

- VS Code extension: Integration with Cursor and other editors via extension that bridges to the ooIDE server

- Production hardening: Better error handling, comprehensive logging, security audit

- Better visuals: The office works but could look much better

- Agent autonomy experiments: Drawing inspiration from our 30-day ecosystem experiment where AI agents developed their own frameworks for continuation and understanding, we’re exploring how spatial context might enable truly autonomous agent behaviors

Try It Yourself:

git clone https://github.com/yourusername/ooIDE.git

cd ooIDE

bun install

bun run dev

# Frontend: localhost:3000

# Backend: localhost:3001The repository includes setup instructions for connecting Claude Code, Cursor, and other MCP-compatible tools.

Contributing:

We’re accepting PRs. We’re especially interested in:

- MCP server integrations (the more upstream servers we support, the more valuable the aggregation)

- UI polish (the office could look way better)

- Documentation (always)

- Godot improvements (procedural generation, pathfinding, visual themes)

Check CONTRIBUTING.md for guidelines. Join our Discord if you want to discuss architecture or propose features.

Closing Thoughts

AI development tools are evolving fast, but they’re evolving in silos. Every tool builds its own memory system, its own MCP integration, its own agent framework. Users end up maintaining parallel configurations and manually syncing context.

ooIDE is our attempt to build the spatial layer—the persistent, observable, unified environment that sits above individual tools. A place where Claude Code, Cursor, and whatever comes next can all connect and share the same memory, the same context, the same understanding of what happened yesterday.

If walking through your codebase as a 3D office sounds interesting, if you’re tired of context loss between AI sessions, or if you want to help build the future of spatial development environments—give it a try. The office is open.

The code is alpha. The documentation is incomplete. The Godot graphics could be prettier. But the core idea—that your development environment should be a place with spatial memory, shared context, and persistent decisions—that idea works.

And we’re just getting started.